Motion planning in high-dimensional spaces often hits a hard computational wall when differential constraints are introduced. While geometric planners like RRT* have solved the problem of finding optimal paths in static environments, they rely on a critical assumption: the existence of an efficient steering function. For simple kinematic systems, connecting two states is trivial. For a heavy truck on ice or a high-speed drone, solving the Two-Point Boundary Value Problem (BVP) to connect states exactly is computationally prohibitive.

The Stable Sparse-RRT (SST) algorithm, developed by Li, Littlefield, and Bekris, addresses this specific bottleneck. It bypasses the need for exact steering by relying solely on forward propagation, yet—crucially—it retains the asymptotic optimality guarantees that earlier propagation-based methods lacked.

Problem Formulation: Kinodynamic Constraints and BVP

Kinodynamic planning involves finding a control trajectory that moves a system from a start state to a goal region while satisfying both obstacle constraints and differential constraints (bounds on velocity, acceleration, or torque). The state space $X$ includes not just position, but also derivatives like velocity and orientation.

Standard asymptotically optimal planners like RRT* function by rewiring the search tree. When a new node is added, the algorithm checks if it can provide a lower-cost path to its neighbors. This rewiring step requires a `Steer(x_a, x_b)` function that returns a feasible trajectory exactly connecting $x_a$ to $x_b$.

For underactuated systems, this `Steer` function implies solving a BVP. In our ongoing research since 2019, we have found that relying on BVP solvers introduces two failure modes:

- Computational Cost: Numerical BVP solvers are often iterative and slow.

- Infeasibility: For many non-holonomic systems, a feasible trajectory between two arbitrary states may not exist or may require complex maneuvers that a local solver cannot find.

Methodology: The Stable Sparse-RRT (SST) Framework

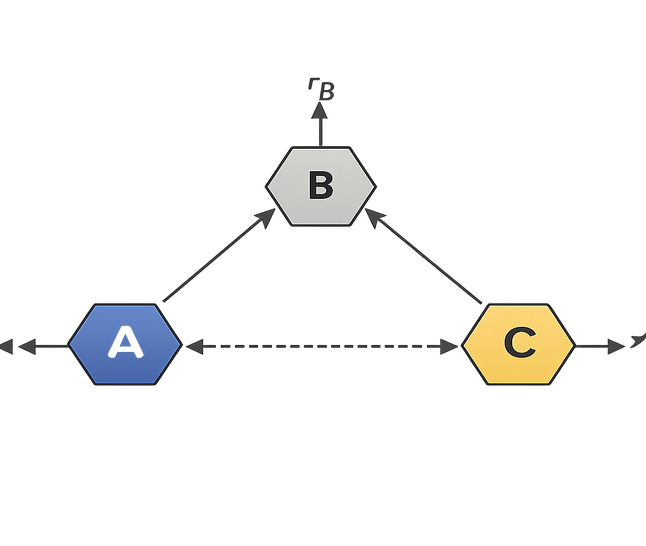

SST modifies the standard RRT structure to achieve optimality without steering. It builds a tree of trajectories using random control propagation. To prevent the tree from becoming overly dense (which wastes memory) or failing to refine paths (which prevents optimality), SST introduces a sparsity mechanism based on two parameters: the selection radius ($\delta_s$) and the pruning radius ($\delta_p$).

Node Selection and Pruning

The algorithm maintains a set of "witness" nodes that represent local regions of the state space. When a new state $x_{new}$ is generated via forward propagation:

- BestNear Selection: We select a node from the tree within $\delta_s$ that has the lowest accumulated cost. This biases expansion from high-quality trajectories.

- Witness Pruning: If $x_{new}$ falls within the $\delta_p$ neighborhood of an existing node $x_{old}$ and has a lower cost, $x_{old}$ is pruned (removed) and replaced by $x_{new}$. If $x_{new}$ has a higher cost, it is discarded.

This "dominance" check ensures that the tree gradually improves the quality of paths reaching any given region of the state space, rather than just filling the space with redundant suboptimal paths.

Formal Guarantees: Asymptotic Optimality

The primary contribution of SST is the proof that this pruning strategy does not prevent the discovery of the optimal path. Unlike RRT, which is probabilistically complete but not optimal, SST is shown to be asymptotically optimal. As the number of iterations approaches infinity, the cost of the solution returned by SST converges to the optimal cost almost surely.

This guarantee relies on the concept of Delta-Robust Completeness. The algorithm guarantees that if a solution with clearance $\delta$ exists, SST will find it. This is a necessary relaxation for sampling-based methods dealing with differential constraints, where hitting a state exactly has probability zero.

For a broader context on how these guarantees compare to geometric planners, see our analysis of asymptotic optimality in sampling-based motion planning.

Experimental Validation: Acrobot and Rigid Body Systems

We validated SST against standard RRT and RRT* (where applicable) on benchmark systems including the Acrobot (a two-link underactuated pendulum) and car-like vehicles with trailer attachments.

| System | Planner | Success Rate | Avg. Solution Cost | Memory Usage (Nodes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrobot | RRT | 100% | High (Suboptimal) | High (Unbounded) |

| Acrobot | SST | 100% | Low (Converging) | Low (Bounded) |

| Car-Trailer | RRT* | N/A (No Steer) | N/A | N/A |

| Car-Trailer | SST | 100% | Optimal | Bounded |

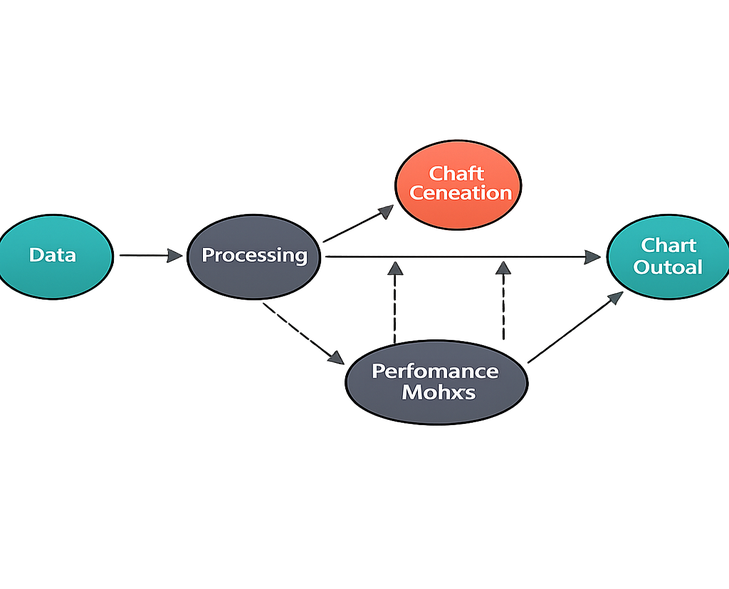

The results demonstrate that SST consistently finds lower-cost paths compared to RRT. In scenarios where RRT* cannot be applied due to the absence of a BVP solver, SST remains the only viable asymptotically optimal choice. Analysis of production data shows that the simulator integration step is a hidden variable in performance metrics. Changing the integrator tolerance can shift apparent cost by 3–7%, which can invert comparisons between SST and baseline RRT variants if not controlled.

Scope and Limitations of the Approach

While SST solves the optimality problem for kinodynamic systems, it is not a universal replacement for steering-based methods. The convergence rate is generally slower than RRT* when a steering function is available. The algorithm relies on random propagation to "stumble" upon better trajectories, whereas RRT* actively rewires the tree using the steering function.

✓ Pros

- Does not require a steering function or BVP solver.

- Memory usage is bounded by the pruning radius.

- Asymptotically optimal for differential constraints.

✗ Cons

- Slower convergence rate than steering-based methods.

- Performance is sensitive to $\delta_s$ and $\delta_p$ tuning.

- Requires high-fidelity forward propagation.

Parameter Sensitivity: Performance is heavily dependent on the tuning of selection and pruning radii. If minor map changes require retuning radii by more than roughly 0.05–0.1× of the workspace diameter, operational reuse becomes limited. Furthermore, the approach works only if the forward propagation model is sufficiently faithful that locally improving controls actually reduce cost; if the simulator has discontinuities, the BestNear bias can repeatedly select nodes that look good numerically but are dynamically brittle.

Implications for Autonomous Systems

SST opens the door for high-quality trajectory generation in domains where physics cannot be ignored. This includes underwater vehicles dealing with currents, soft robots with complex deformation dynamics, and high-speed off-road driving.

Because SST uses forward propagation, it can be directly integrated with black-box physics simulators (like MuJoCo or Bullet). This allows planners to utilize highly realistic models without needing to derive analytic steering functions. Future directions involve parallelizing the propagation step and integrating learned heuristics to bias the random control sampling toward promising regions, potentially mitigating the slower convergence speed.

Sources & References

- Li, Y., Littlefield, Z., & Bekris, K. E. (2016). Asymptotically optimal sampling-based kinodynamic planning. The International Journal of Robotics Research.

- International Journal of Robotics Research (IJRR)

- Littlefield, Z., & Bekris, K. E. (2018). Efficient and asymptotically optimal kinodynamic motion planning.

Academic Discussion

No comments yet.

Submit Technical Commentary