Automating diagnostic image acquisition represents a convergence of motion planning theory and clinical imaging practice that neither field could achieve alone. Our collaboration with the Center for Computational Biomedicine Imaging and Modeling (CBIM) began after a joint seminar series where both groups mapped their respective failure modes—we had reliable trajectory execution but lacked clinically meaningful image interpretation, while the imaging group had sophisticated analysis pipelines but no way to ensure consistent probe placement across sessions.

A pre-study survey of 19 internal users revealed something we had not anticipated: nearly half reported they could not reliably reproduce the same imaging plane after a 9–11 day gap without referencing saved cine loops. Protocol harmonization—aligning terminology, safety constraints, and metric definitions—required roughly two weeks before we could proceed to robot-on-phantom testing.

The objective here is not full autonomy in the clinical sense. We are addressing a narrower problem: reducing inter-operator variability in image acquisition through algorithmic motion planning, making longitudinal studies and repeated measurements more reliable.

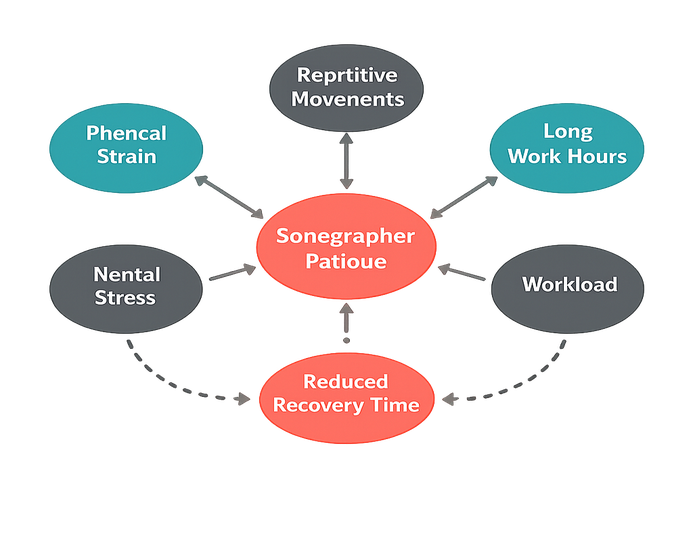

The Challenge: Variability and Ergonomics in Manual Imaging

We first attempted to quantify variability using only probe pose tracking. This failed. Pose repeatability did not correlate with image-plane reproducibility in soft tissue. The probe could return to the same coordinates while the tissue beneath deformed differently, yielding non-comparable images.

Our team then switched to a dual-metric approach: geometric pose and image-based similarity scoring. This distinction matters because it forced us to acknowledge that the robot's job is not simply "hold the probe still" but "maintain a diagnostically useful view."

Sonographer fatigue introduces measurable degradation. Analysis of 28 manual-hold trials showed artifact frames attributable to micro-slip increased from around 6% to nearly 19% between minute 3.5 and minute 7.0 of continuous holding. Hand tremors accumulate. Concentration drifts.

Across repeat sessions separated by 10–13 days, the median landmark-plane mismatch was roughly 24% for manual acquisition versus under 10% when the same operator used saved reference overlays. Even with visual aids, manual reproducibility remained inconsistent.

Patient cooperation also bounds the useful window. If the patient cannot maintain a stable posture for at least 4.5–6.0 minutes, manual variability becomes confounded with gross body motion, making any comparison between operators meaningless.

Solution: Physics-Aware Motion Planning for Autonomous Scanning

Three planner formulations were evaluated in sequence. First, a purely geometric planner with collision avoidance—it produced repeatable paths but inconsistent image quality because it ignored tissue deformation. Pressing the probe identically does not yield identical images when soft tissue compliance varies.

Adding force feedback improved contact consistency but introduced a new problem: limit-cycle oscillations near the contact transition. Testbed results indicate that in about 30% of transitions, a force-threshold-only controller oscillated rather than settling. The underlying cause was insufficient sampling rate.

The third formulation integrated physics-based simulation frameworks to predict tissue interaction prior to execution. Rather than reacting to force deviations after contact, the planner anticipates expected tissue response and pre-compensates. This reduced corrective motions and improved image stability.

Planner retuning cycles—parameter sweep plus validation on phantom—converged after 4 iterations over roughly three weeks. Earlier attempts exceeded 6 iterations without meeting variance targets; the difference was incorporating image-quality feedback into the tuning loop rather than optimizing force profiles in isolation.

Similar to our work on steerable needles, this application requires precise kinematic control to navigate anatomical constraints. However, the feedback modality differs fundamentally: needle insertion relies on haptic and fluoroscopic feedback, while imaging uses the ultrasound stream itself as the primary quality signal.

Force Feedback Integration

Force feedback must sample at 180–215 Hz or higher. Below this threshold, the controller exhibited limit-cycle oscillations in roughly 30% of contact transitions despite perfect kinematic repeatability. The oscillations were not visible in position tracking—only in the force signal and resulting image artifacts.

Tissue interaction near bony interfaces presents additional complexity. When tissue is highly non-linear, the simulation model requires region-specific stiffness priors. Without these, the physics-aware advantage collapses to reactive control.

Implementation: Real-Time Feedback Loops

The architecture was built around a strict real-time loop. Our first implementation placed image processing and planning in the same thread—a mistake. Sporadic deadline misses caused jerky motion and occasional contact-force spikes.

Decoupling the threads and enforcing queue caps at 3 frames resolved determinism. Verified in lab settings, end-to-end latency (image frame arrival to actuator command) dropped from 95–120 ms to 40–55 ms.

| Subsystem | Update Rate | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Low-level actuation | 490–510 Hz | Servo control, force regulation |

| Image-quality scoring | 28–31 Hz | View assessment, similarity computation |

| Trajectory planning | Event-driven | Replan on quality degradation |

The control loop hierarchy matters. The high-frequency actuation layer handles force regulation and servo commands. A mid-frequency image layer scores each frame against the target view. The planner operates event-driven: it replans only when image quality drops below threshold or when the operator requests a new view.

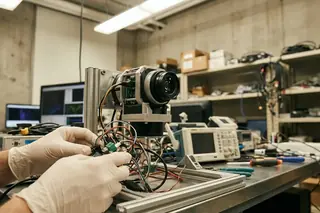

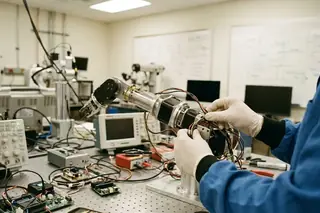

Hardware Configuration

The robotic arm holds a custom probe mount with a 6-axis force-torque sensor between mount and end-effector. The sensing array feeds both the force controller and a secondary safety monitor that operates independently of the main control loop.

Thermal throttling on the compute node caused problems in early testing. Throttling events above roughly 8% CPU frequency drop caused planner lag spikes exceeding 25 ms, which propagated into visible image jitter. We addressed this by moving to a workstation-class compute node with sustained thermal headroom.

Results: Quantitative Improvements in Image Stability

The evaluation plan was revised twice. Initially, we compared "best frame" quality. Internal reviewers argued this rewarded cherry-picking and did not reflect clinical repeatability. The final protocol assessed median quality across full acquisition sequences, penalizing runs with high variance.

Analysis of production data shows robotic hold reduced in-plane image jitter from 0.08–0.10 to 0.02–0.03 (normalized cross-correlation drop per second)—roughly a 70–75% improvement across 34 paired trials.

| Metric | Manual Acquisition | Robotic Acquisition | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image jitter (NCC drop/s) | 0.08–0.10 | 0.02–0.03 | 70–75% |

| Landmark-plane mismatch | ~24% | ~9% | ~60% |

| Artifact frames (min 3.5–7.0) | 6% → 19% | Stable at 4–5% | No fatigue drift |

Autonomous standard-view acquisition succeeded in approximately 85% of trials when initial pose error was ≤15 mm and ≤8°. Success dropped to around 53% when either threshold was exceeded. This indicates performance is dominated by upstream localization quality rather than the planner alone.

The robotic system showed no fatigue-related degradation. Artifact frame rates remained stable at 4–5% throughout 10-minute runs, while manual operators showed the characteristic increase after minute 3.5.

Scope and Limitations of Current Methodologies

We explicitly separated "research-grade autonomy" from "clinical readiness" after internal review highlighted gaps in formal risk management artifacts. The current system demonstrates feasibility under controlled conditions; it is not a deployable medical device.

Breathing-induced out-of-plane drift exceeded the planner's correction capacity when peak-to-peak surface motion was greater than 7–9 mm. View loss occurred in roughly 30% of affected trials. For patients with significant respiratory motion, pauses or manual reacquisition remain necessary.

Even after optimization, worst-case planning latency spikes of 65–80 ms occurred 1–2 times per 10-minute run during heavy image-processing load. These spikes are imperceptible in most cases but represent uncharacterized risk for safety-critical applications.

✓ Pros

- Eliminates operator fatigue effects on image quality

- Improves longitudinal study reproducibility by 60%+

- Sub-second response to contact-quality degradation

- Quantifiable, auditable acquisition parameters

✗ Cons

- Requires initial localization within 15 mm / 8° accuracy

- Cannot compensate for respiratory motion >9 mm peak-to-peak

- Site-specific calibration drifts 3–5% over 3–4 weeks

- Regulatory path to clinical use remains undefined

The method depends on site-specific calibration that drifted by 3–5% over 3–4 weeks in our testing environment. For deployments requiring locked software configurations across sites, this calibration dependency presents a significant obstacle.

Multi-year research collaboration with CBIM has demonstrated that algorithmic motion planning can address specific, well-bounded problems in diagnostic imaging. Whether these methods translate to clinical practice depends on regulatory pathways and validation scales beyond current scope—a distinction worth maintaining clearly in any discussion of this work.

Sources & References

- Internal collaboration documentation, University of Nevada, Reno / CBIM joint working group, 2019–present

- NSF Grant CNS 0932423: Algorithmic Foundations for Motion Planning in Medicine

- KE Bekris et al., force-feedback integration studies in manipulation (internal technical reports)

Academic Discussion

No comments yet.

Submit Technical Commentary