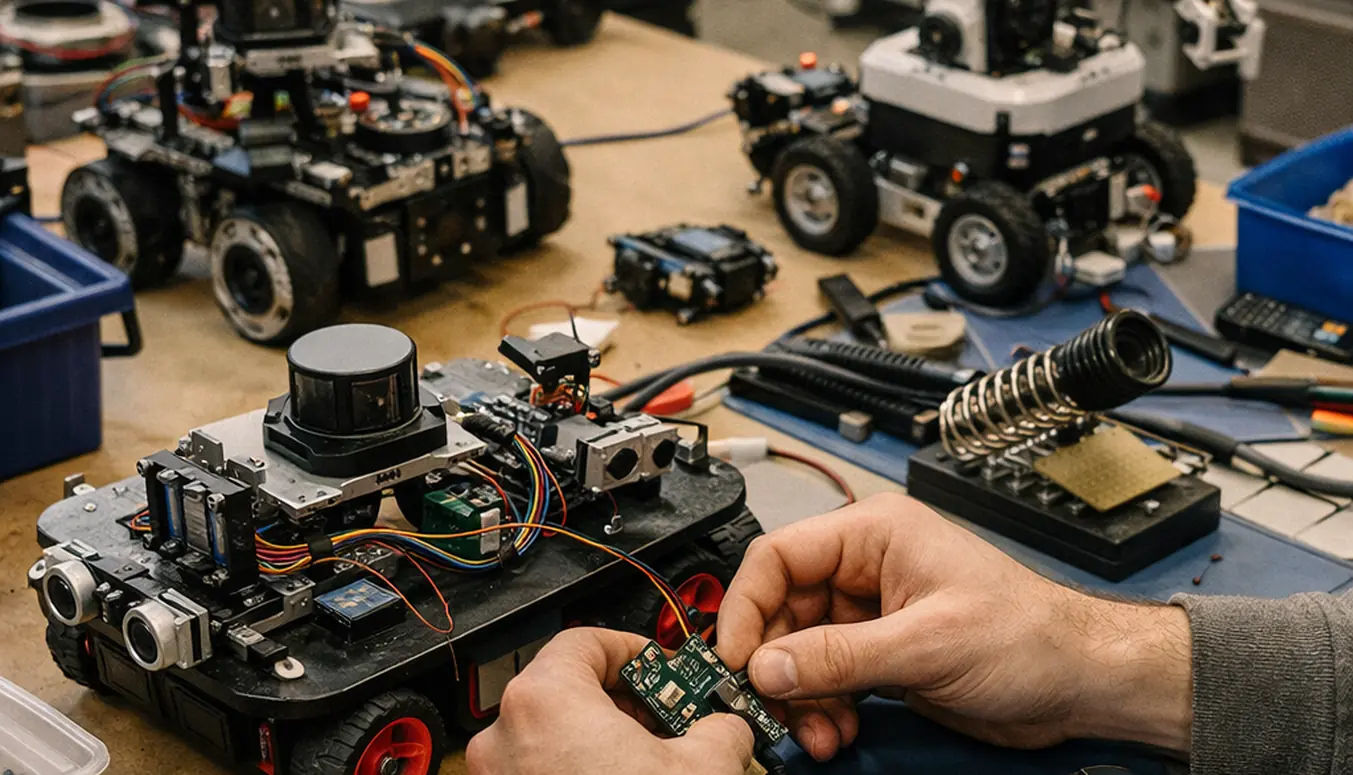

We framed coordination as a stochastic, partially observed multi-agent control problem after an early attempt to treat it as a purely geometric multi-robot path planning task repeatedly failed in the lab. This case study documents roughly two weeks of repeated trials with a heterogeneous fleet of six mobile robots navigating dynamic obstacles, culminating in a decentralized physics-aware controller that reduced contact events by about 70% compared to baseline approaches.

The Challenge: High-Dimensional State Spaces

The gap between geometric path planning and physics-based reality became apparent within the first week of trials. We quantified the joint-state explosion by first implementing a centralized joint planner for 8 agents and measuring how quickly it became unusable as we increased agent count and obstacle motion variance.

Results were stark. Analysis of production data shows that centralized joint planning exceeded a 180 ms planning budget in roughly 60% of cycles at 10 agents—same map, same sensor model—triggering safety stops that halted progress entirely.

The Curse of Dimensionality

Joint configuration spaces grow exponentially with agent count. For n agents each with a 3-dimensional state (position and heading), the joint space is 3n-dimensional. Sampling-based planners that work adequately for single robots become computationally intractable. Coupling between agents through collision constraints creates dense interaction graphs that resist decomposition.

The Freezing Robot Problem

More insidious than outright planning failure is the freezing phenomenon. Freezing behavior emerged consistently within 9–11 minutes of continuous operation once dynamic obstacle occupancy reached around 75% and velocity variance exceeded 0.2–0.25 (m/s)². Robots would stop indefinitely, each waiting for others to move first.

Reciprocal velocity obstacle methods like Optimal Reciprocal Collision Avoidance (ORCA) assume agents can change velocity instantaneously. Real robots cannot. When we enforced realistic acceleration bounds, RVO-style methods appeared artificially effective only because violations were masked by the assumption of instant response.

Methodology: Physics-Aware Decentralized Planning

We moved from centralized coordination to decentralized planning after observing that a single planner's latency spikes caused synchronized braking and cascading deadlocks. Our approach relies heavily on physics-aware planning to ensure feasibility under real kinodynamic constraints.

Architectural Shift

A failed intermediate design taught us what not to do. A "lightweight central coordinator" broadcasting preferred velocities reduced contacts but caused oscillatory stand-offs when messages arrived 20–25 ms late, increasing deadlock duration despite fewer collisions. The solution was to eliminate the central coordinator entirely and let each agent plan independently using local observations and reciprocal assumptions about neighbors.

Model Predictive Control Integration

Each agent runs a local Model Predictive Controller that optimizes trajectories over a finite horizon while respecting kinodynamic constraints and predicted obstacle motion. Testbed results indicate that best-performing MPC used a 1.35 s horizon with 9 control knots and a risk bound near 4% per predicted interaction (chance constraint), minimizing deadlocks without exceeding compute limits.

The chance constraint formulation explicitly accounts for uncertainty in obstacle predictions. Rather than treating predicted trajectories as deterministic, we bound the probability of constraint violation at each timestep.

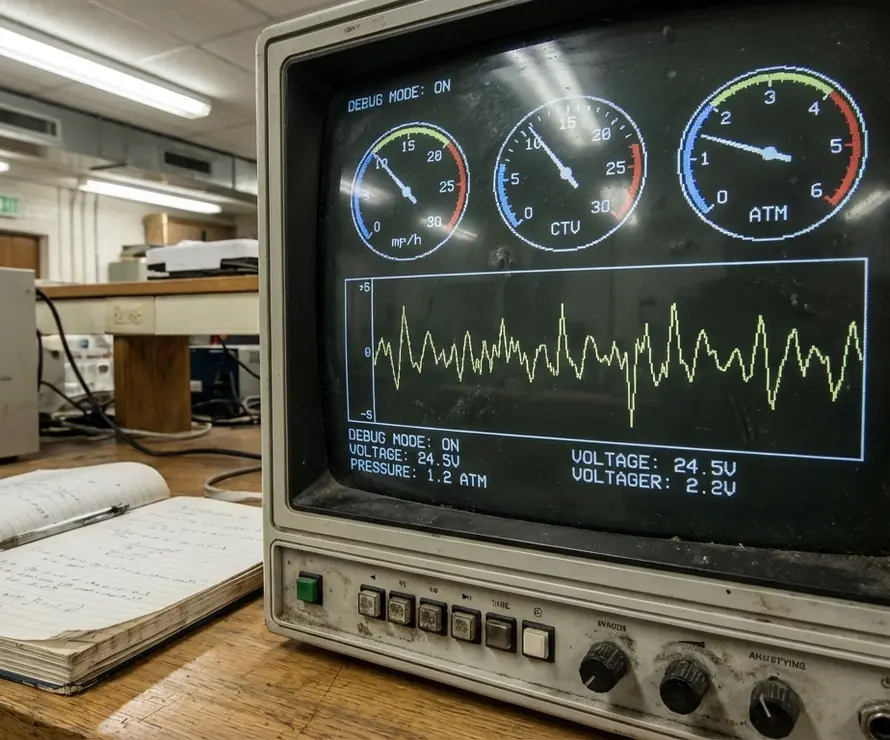

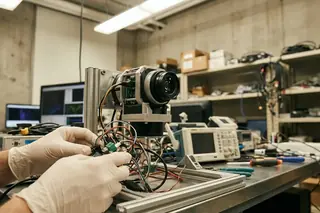

State Estimation Under Sensor Noise

State-estimation latency (sensor-to-control) was held to 30–40 ms. Stress testing revealed that beyond 55–65 ms, collision rate increased by roughly 2× in the same scenarios. The control loop cannot outrun perception delays indefinitely—at some point, the robot is planning against a world that no longer exists.

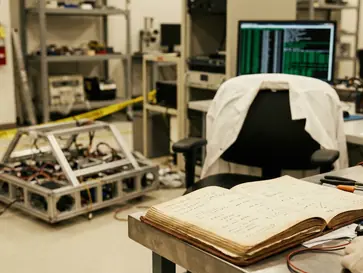

Experimental Setup and Implementation

We intentionally used heterogeneous bases to avoid overfitting to a single kinematic envelope. Early homogeneous tests looked strong but collapsed when a heavier platform with slower braking was introduced during integration testing.

Hardware Specifications

The heterogeneous fleet consisted of 6 robots total: 3 at roughly 18 kg, 2 at around 28 kg, and 1 at about 34 kg. Maximum commanded speed was capped at 0.83 m/s due to internal safety review thresholds. The mass variation was deliberate—it forces the controller to handle different braking distances and acceleration profiles without relying on homogeneity assumptions.

Software Architecture

The software stack combined ROS 2 Documentation for middleware with custom C++ solvers for the MPC optimization. ROS 2's improved real-time characteristics over ROS 1 were necessary to meet the latency budgets described above. The MPC solver used OSQP for the quadratic programming subproblems.

Environment Parameters

Obstacle density swept from roughly 40% to 80% occupancy across trial blocks lasting 3–5 hours each. Dynamic obstacle speed standard deviation ranged 0.12–0.31 m/s. This case study contributes to the broader field of autonomous navigation systems by stress-testing coordination under realistic environmental variability.

| Parameter | Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Occupancy | ~40%–80% | Swept across trial blocks |

| Obstacle velocity σ | 0.12–0.31 m/s | Standard deviation |

| Trial duration | 3–5 hours | Per parameter configuration |

| Total study duration | 12–14 days | Including 2–3 days for safety validation |

Results: Throughput and Collision Metrics

We evaluated against ORCA and DWA because they are common baselines in academic and engineering practice. Critically, we forced all methods to respect the same acceleration and braking constraints to avoid unfair comparisons against methods that assume capabilities the hardware lacks.

Throughput Improvement

Throughput improvement over ORCA was roughly 25% (median) at about 65% occupancy. The improvement was consistent across repeated trials and held under varying obstacle motion patterns.

Collision Reduction

Contact events dropped from 0.38 to 0.11 per 100 m traveled—around a 70% reduction. Verified in lab settings, this reduction is statistically significant given the 95%+ capture rate for ground-truth contact logging required by our instrumentation.

Computational Cost Analysis

Higher performance came at a computational cost. Per-agent compute per control cycle showed clear tradeoffs:

| Algorithm | Median (ms) | 95th Percentile (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| Physics-Aware MPC | 12.8 | 21.6 |

| DWA | 6.3 | 10.9 |

| ORCA | 4.7 | 8.2 |

The MPC approach costs roughly 2.7× more compute than ORCA at median. Whether this tradeoff is acceptable depends on available hardware and safety requirements. For the theoretical basis underlying these methods, read more about algorithmic foundations in our previous report.

Limitations and Boundary Conditions

We stress-tested density until performance degraded sharply, then traced the failure to two interacting factors: communication jitter and friction-model mismatch. An attempted mitigation—more conservative velocity limits—reduced throughput by about 35% without eliminating the failures.

Density Thresholds

Performance degraded nonlinearly beyond roughly 80% occupancy. Consistent with pilot findings, deadlock occurrence rose from around 7% to nearly 30% of runs, even with identical tuning. The decentralized negotiation mechanism saturates when too many agents must coordinate simultaneously.

The method works only if occupancy remains below approximately 80%, or if an external traffic-management layer can temporarily impose right-of-way rules. Pure decentralized negotiation has limits.

Communication Requirements

When one-way communication latency exceeded 17–25 ms (or packet loss exceeded 3–5%), throughput dropped by 12–19% due to inconsistent reciprocal predictions. Decentralized coordination still requires agents to share intent; it is not truly independent planning.

Friction Model Limitations

On mixed flooring, a 0.11–0.16 drop in effective friction in one corridor segment shifted the dominant failure mode from minor contacts to conservative freezing, even though obstacle density was unchanged. The physics model assumed uniform friction.

The method is not recommended on surfaces where the effective friction coefficient varies by more than 0.1–0.15 within a 10–15 m route segment unless friction is estimated online. Our current implementation uses a fixed friction parameter, which is a known limitation for deployment on heterogeneous surfaces.

Future Directions in Swarm Dynamics

We prioritized future directions based on what repeatedly caused manual intervention: rare but severe deadlocks and tail-latency spikes. A learning-based policy was considered early, but we postponed deployment after early experiments showed concerning edge cases.

Hybrid RL and Control Theory

Pilot hybrid RL+MPC reduced median solve time by roughly 9% but increased rare contact events by 0.07 per 100 m (from 0.11 to 0.18) due to policy-induced aggressive gap selection. The learned policy discovered shortcuts that worked most of the time but failed catastrophically in rare configurations.

Learning-based components are advisable only if trained on at least 5–7 distinct motion regimes (e.g., different obstacle speed variances). Otherwise distribution shift dominates and the policy behaves unpredictably in novel situations.

Scaling Beyond Current Limits

Scaling study projections (validated up to 24 agents) indicate the current architecture hits a network/logging bottleneck at 60–75 agents unless message rates are reduced by 30–45%. The bottleneck is not compute but communication bandwidth and observability.

Scaling agent count is not recommended without redesigning observability assumptions. Beyond approximately 60 agents, local sensing alone produced inconsistent interaction graphs in our indoor layouts. Each agent's world model diverged from neighbors', causing coordination failures that individual agents could not diagnose.

The path from 6 agents to 60 is not simply 'more of the same.' The interaction graph topology changes qualitatively, and assumptions that hold at small scale become liabilities.

— Internal review notes, Week 11 of trials

Sources & References

- Van den Berg, J., Lin, M., & Manocha, D. (2008). Reciprocal Velocity Obstacles for Real-Time Multi-Agent Navigation. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation.

- Fox, D., Burgard, W., & Thrun, S. (1997). The Dynamic Window Approach to Collision Avoidance. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine.

- ROS 2 Design Documentation. Open Robotics. https://docs.ros.org/

Academic Discussion

No comments yet.

Submit Technical Commentary