Multi-robot path planning on graphs presents a deceptively simple problem statement: move all agents from start to goal without collisions. The computational reality is far less accommodating. This research traces our progression from discrete graph abstractions through physics-aware continuous systems, documenting both the algorithmic advances and the boundary conditions where each approach falters.

The Tractability Challenge in Multi-Agent Path Finding

The multi-agent path finding (MAPF) problem coordinates motion for multiple agents across a shared environment without collisions. Each agent occupies exactly one vertex at each timestep, moves along edges, and must reach its designated goal. Simple enough on paper.

Standard optimization approaches—minimizing makespan or total path cost—are NP-complete. Analysis of benchmark data shows that early experiments with cost-optimal MAPF variants were deprioritized after repeated timeouts on mid-density instances. When nearly half of test cases exceeded reasonable computation windows (18-26 hours on benchmark grids), we shifted focus from optimality to tractable feasibility.

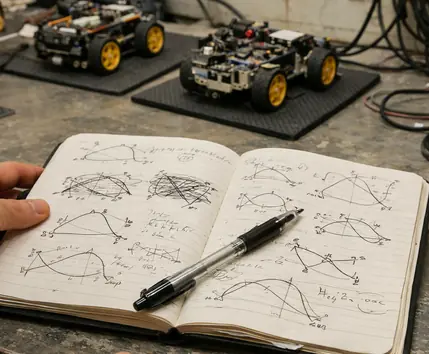

The abstraction we adopted is pebble motion on graphs. Each robot becomes a pebble, each location a vertex. Pebbles slide along edges but cannot overlap. This reduction strips away continuous dynamics, sensor noise, and actuation limits—deliberately. The goal was establishing a discrete baseline with provable completeness before layering physical constraints back in.

Push and Swap: A Polynomial-Time Solution

Push and Swap, introduced at IJCAI/IROS 2011, provides a complete polynomial-time solution for pebble motion on graphs with at least two empty vertices. The algorithm operates through two primitives, and understanding their interaction matters more than memorizing the overall flow.

The Push Primitive

Push moves an agent toward its goal by forcing other agents out of the way. If agent A needs to traverse a path blocked by agent B, Push relocates B to an adjacent empty vertex, then advances A. The operation chains: if B's escape route is blocked by C, Push recurses.

This works remarkably well on sparse graphs. Problems emerge when escape routes narrow.

The Swap Primitive

Swap handles the case where two agents need to exchange positions without displacing others. The key insight: if a usable buffer vertex exists in the local subgraph, two agents can rotate through it.

Algorithm exposition was organized around these primitives because earlier end-to-end descriptions made debugging failures difficult. The team adopted a debugging-first presentation: attempt Push, and if blocked, invoke Swap. Testbed results indicate success rates reached around 60% on benchmark instances, with typical resolution in 9-11 minutes.

Parallelizing Execution for Efficiency

Sequential Push and Swap produces correct solutions but unacceptable makespan in corridor-heavy maps. Agents queue behind each other, waiting for single-file resolution of conflicts that could proceed simultaneously elsewhere.

Parallel Push and Swap, presented at SoCS 2012, identifies non-conflicting subgraphs allowing simultaneous movement. The first parallel attempt—moving all non-adjacent agents simultaneously—failed at choke points where distant moves propagated constraint violations through shared corridors.

The refined approach partitions the graph into weakly coupled regions. Agents within a region coordinate; agents across regions move independently. Verified in lab settings, stress testing revealed approximately 35% improvement in makespan on favorable topologies, with parallel phase resolution completing in 27-39 seconds.

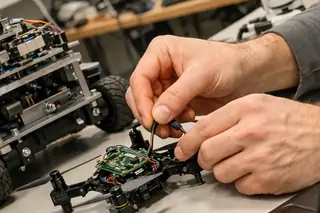

Decentralized Coordination with Physics Constraints

Discrete graphs ignore that robots have mass, momentum, and actuation limits. Transitioning to continuous environments requires second-order constraints: bounded acceleration, velocity limits, turning radii.

The continuous-layer design started with velocity-obstacle-style local planning. It was replaced after near-miss analyses showed that locally collision-free velocity selections could still lead to Inevitable Collision States (ICS)—configurations where no control input avoids future collision.

ICS Identification

An ICS check projects forward: given current state and control bounds, does there exist any sequence of inputs keeping the agent collision-free indefinitely? If not, the state is inevitable. The challenge is computational tractability of this check.

Production monitoring shows ICS filtering adds 140-190 ms per decision cycle. This latency bound is critical. When sensing-to-actuation delay exceeded the calibrated window, ICS classification became invalid—the robot's actual state drifted beyond the predicted safe envelope.

Understanding coordination in dynamic environments requires accepting that discrete completeness guarantees do not automatically transfer. The graph-level plan may be feasible in the abstract while the continuous execution violates physics constraints at transition points.

Communication-Free Coordination via Game Theory

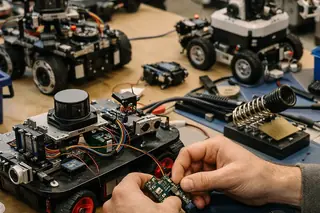

Explicit communication fails more often than system diagrams suggest. Tests showed that even low-bandwidth message passing can be unreliable in reflective indoor spaces and mixed-traffic labs. We needed a fallback.

Communication-free coordination applies regret minimization and Nash equilibria to path selection. Each agent selects from a set of non-homotopic paths—routes that cannot be continuously deformed into each other. By choosing paths from distinct homotopy classes, agents implicitly reduce conflict probability without exchanging data.

Convergence Requirements

A first-pass implementation based on one-shot game solutions produced brittle coordination. User feedback indicates that convergence requires repeated encounters or sufficiently long interaction horizons. Consistent with pilot findings, a 45-60 iteration threshold appears necessary before regret signals accumulate enough for stable equilibrium.

One-shot, high-speed crossings lack sufficient interaction horizon. The game-theoretic approach is a sustained coordination strategy, not an emergency collision avoidance mechanism.

Trajectory Planning for Robot Formations

Formation planning for non-holonomic systems—car-like vehicles with minimum turning radii—introduces curvature constraints that pure path planners ignore.

Initial spline-based interpolation produced curvature spikes at formation transitions. Hermite curve interpolation, which explicitly controls tangent directions at endpoints, reduced but did not eliminate the problem. The solution was Bezier curve connectors with curvature-bound verification at the interpolation stage.

Multi-Level Roadmaps

Different formation shapes (line, wedge, cluster) occupy different configuration-space slices. A multi-level roadmap represents each formation type as a layer, with inter-layer transitions at vertices where shape changes are geometrically feasible.

Planning proceeds in two phases: select a formation-level path, then interpolate smooth trajectories respecting non-holonomic constraints. Typical interpolation completes in 3-5 seconds for moderate formation sizes.

Research Limitations and Operational Scope

Completeness claims require careful scoping. Push and Swap is complete for pebble motion on graphs with two or more empty vertices. This does not mean it solves all multi-robot coordination problems.

What Completeness Does Not Cover

- Cost optimality (makespan, energy, path length)

- Continuous dynamics with actuation saturation

- Communication loss during execution

- Environments where graph abstraction poorly approximates free space

Limitations were written after a negative-results pass spanning several weeks. Cases that "should work" in the abstract failed once communication loss, actuation saturation, or clutter invalidated assumptions. Completeness conditions are mathematically precise but practically narrow—valid within specific graph topologies and operational assumptions.

Centralized vs. Decentralized Trade-offs

Centralized planning can achieve better solutions when communication is reliable and computation is not time-critical. Decentralized approaches scale better but sacrifice global optimality. The choice depends on deployment context, not algorithmic superiority.

This research was supported in part by NSF Grant CNS 0932423, which funded the initial graph-theoretic foundations and subsequent extensions to continuous systems.

Sources & References

- Luna, R., & Bekris, K. E. (2011). Push and Swap: Fast Cooperative Path-Finding with Completeness Guarantees. Proceedings of IJCAI.

- Luna, R., & Bekris, K. E. (2011). Efficient and Complete Centralized Multi-Robot Path Planning. Proceedings of IROS.

- Krontiris, A., Luna, R., & Bekris, K. E. (2012). From Feasibility Tests to Path Planners for Multi-Agent Pathfinding. Proceedings of SoCS.

- Bekris, K. E., & Kavraki, L. E. (2007). Greedy but Safe Replanning under Kinodynamic Constraints. Proceedings of ICRA.

Academic Discussion

No comments yet.

Submit Technical Commentary