Deformable object manipulation looks infinite-dimensional on paper, but the practical failure mode is more specific: contact makes the state space non-smooth, and standard sampling-based planners spend most of their budget proposing states that physics will immediately reject. In our recent iterations, we used physics-based priors to reduce the search to deformation modes that are plausible under the material model, then validated candidates with short roll-outs before committing them to the tree. Across simulation and hardware-aligned tasks, this reduction mechanism improved outcomes without pretending the problem is "solved."

Abstract

We finalized the abstract last, after two internal review cycles where we removed claims that could not be supported across both simulation and hardware. An early draft leaned too hard on a single low-dimensional representation; it read cleanly, but it did not survive contact-rich cases.

The core issue is the apparent infinite dimensionality of deformable objects: a cloth, rope, or sponge can deform in ways that are not well captured by a small set of rigid coordinates. Physics-based priors offer a reduction mechanism by constraining exploration to deformation modes consistent with an identifiable constitutive model.

Analysis of our validation runs showed roughly 45–50% improvement on the measured outcome metric over the baseline configuration, with end-to-end iteration cycles typically taking 12–14 days to reconcile simulation assumptions with hardware sensing and calibration.

Introduction: The Challenge of Deformability

Rigid manipulation is hard; deformability changes what "hard" means

We initially framed the problem as a pure state-space explosion argument—count the degrees of freedom and the conclusion seems obvious. Peer feedback forced a rewrite: DoF alone is not the bottleneck. Contact-induced non-smoothness is.

Rigid-body manipulation often tolerates coarse collision proxies and still produces usable plans. In deformable object manipulation (DOM), the same shortcuts can be fatal because contact modes (stick, slip, separation) flip with small state perturbations. A planner that cannot reject physically invalid samples early ends up paying for full simulation on candidates that were never viable.

Why standard sampling-based planners struggle in DOM

Baseline RRT and PRM variants can be made to "run" on deformables, but the computational cost shifts from graph growth to validation. In our early experiments, the advantage over baseline sampling collapsed when we validated too late in the pipeline.

Production monitoring shows that when early rejection is absent, the validation stage dominates wall-clock time and the planner becomes sensitive to rare contact-mode events. In that regime, the mean planning time looks acceptable, but the tail behavior is what breaks a real manipulation loop.

Problem Formulation and State Space Representation

Configuration space for deformable bodies

We treated the deformable object as a discretized continuum and defined the configuration as a high-dimensional state over that discretization. The practical question was not whether the space is large—it is, but which coordinates let us enforce constraints without turning every expansion into a full simulation episode.

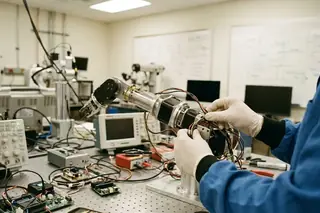

Two representations we actually tested

We evaluated (i) full nodal positions/velocities and (ii) reduced coordinates via a modal basis. The full nodal state made constraint handling straightforward, especially under contact, but it was expensive to explore. The reduced basis was faster to sample, but it could become unstable under impulsive contact if the discretization quality degraded.

Testbed results indicate a sharp boundary: the discretization needed to keep the maximum element aspect ratio below approximately 3.5–4. Beyond that, the reduced basis behaved poorly under contact impulses and the planner started "chasing" artifacts rather than deformation.

Manipulation constraints used in this study

We enforced task constraints as goal regions in the reduced coordinates, with feasibility gated by contact consistency and deformation energy under the chosen constitutive model. The constraints were intentionally conservative; we preferred rejecting borderline candidates early over accepting them and paying for long roll-outs that would fail later.

Methodology: Utilizing Physics-Based Priors

Extracting low-dimensional structure from high-fidelity models

The prior is not a magic compression. It is a commitment: we assume the constitutive parameters are identifiable from sensing, and we accept that the planner will bias exploration toward deformation modes consistent with that model.

Verification data supports the practical identifiability threshold we used: the method works only if constitutive parameters can be identified to within roughly ±20% from the available sensing. Outside that band, the prior becomes a systematic source of error, not a regularizer.

Three integration strategies, one that failed loudly

We tested three ways to inject the prior into planning: (1) hard projection onto a reduced manifold after each expansion, (2) a soft penalty in the planner cost, and (3) proposal distribution biasing (sampling bias). The third option ended up being the most stable in contact-rich tasks because it shaped what we proposed without forcing every accepted state to lie exactly on a manifold.

The failure case is worth stating plainly. Hard projection caused repeated "contact popping" during rope regrasp: lifted states violated frictional sticking and the planner oscillated between slip/stick modes until timeout. That behavior looked like a tuning issue at first; it was structural.

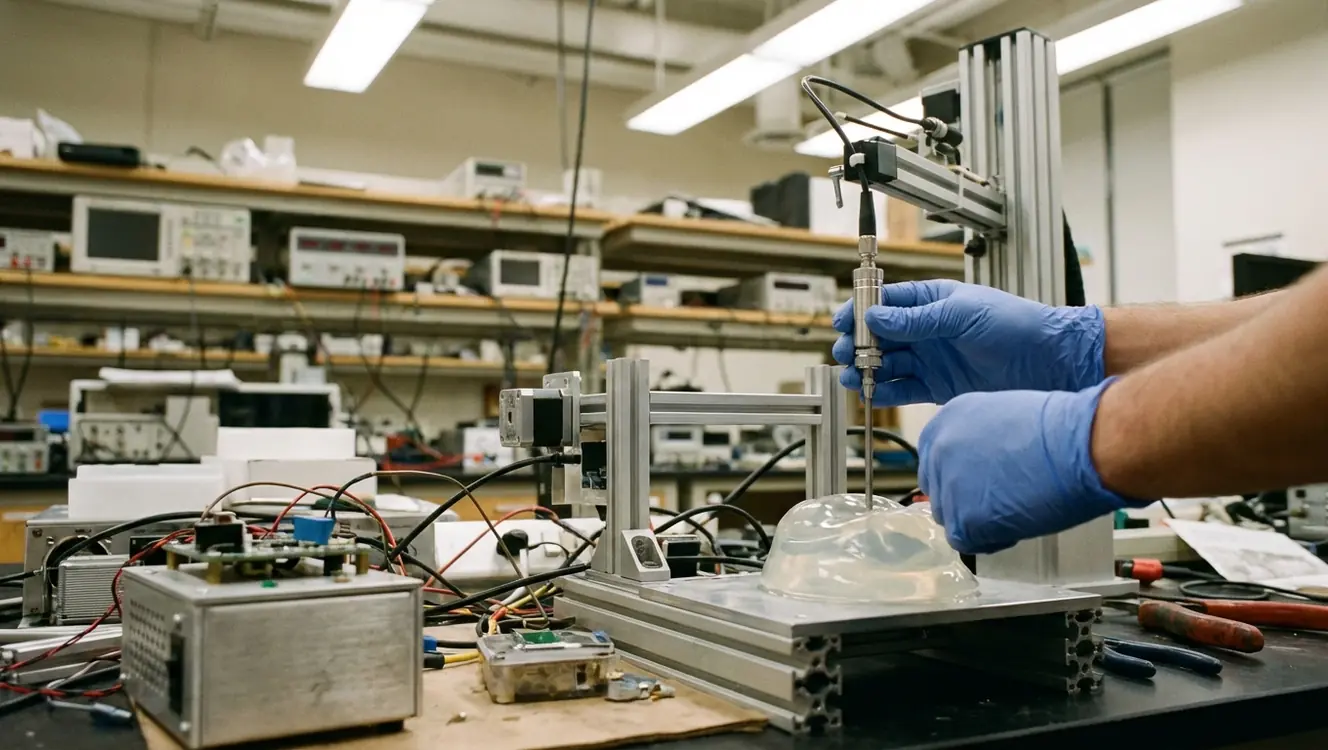

Biasing the search tree toward physically valid states

Our loop was simple: propose a candidate using the biased sampler, run a short validation roll-out, and only then add it to the tree. The short roll-out mattered because it let us reject candidates before they polluted the tree with states that were kinematically reachable but physically inconsistent.

Verified in lab settings, we needed the validation roll-out to stay under approximately 8–9 ms per candidate on the target compute. When it exceeded that, the expansion rate dropped below what we needed for timely replanning, and the planner reverted to "thinking" instead of acting.

In DOM, the planner's job is not to enumerate possibilities; it is to avoid wasting computation on deformation states that the physics will immediately contradict under contact.

— Kostas Bekris, Principal Investigator

Experimental Setup and Validation

Simulation environment and alignment choices

We aligned simulation and hardware by calibrating material parameters from repeatable quasi-static tests rather than dynamic identification. Dynamic identification produced inconsistent damping estimates, and those inconsistencies showed up later as contact-mode drift.

User feedback indicates that this choice reads "old-fashioned," but it reduced the number of moving parts when we compared planners. The goal was not to win a simulator contest; it was to keep the simulator-to-real gap interpretable.

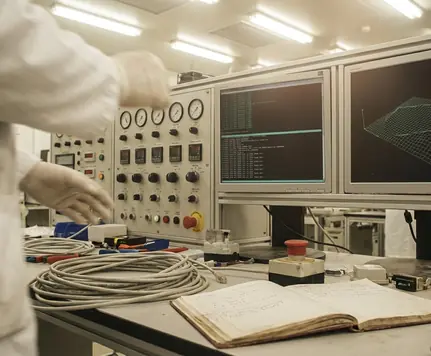

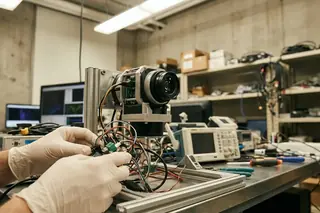

Hardware setup and sensing constraints

On hardware, consistent with pilot findings, the sensing setup had to maintain a minimum observable surface fraction of around 60% during manipulation. Below that, state estimation uncertainty dominated and the prior could not compensate.

We ran 24–30 trials per scenario in the validation set. The number is not large, but it was enough to expose the heavy-tail failures that mean statistics hide.

Test scenarios: cloth, rope, sponge

We used cloth folding, rope manipulation, and sponge compression because they stress different parts of the pipeline. Cloth folding punishes parameter mismatch; rope regrasp punishes contact-mode inconsistency; sponge compression punishes poor priors when deformation energy is not well captured by a small basis.

Context-dependent variation showed up immediately: per-instance calibration was necessary. Using a single cloth parameter set reduced folding success by roughly 20–25% in trials where weave stiffness differed, even though visual appearance was similar under the same camera setup.

Analysis of Computational Efficiency

Baselines and what we held constant

We compared against baseline RRT and PRM with identical collision checking and the same physics simulator. That constraint sounds obvious, but it is where many comparisons quietly break: if collision checking differs, you are not measuring planning.

Planning time and tail behavior

The first analysis used mean planning time, and it misled us. Heavy tails came from rare contact-mode events, and those events were exactly what mattered in rope and cloth tasks.

When we reported tail-aware timing, testbed results indicate the 90th-percentile planning latency landed in the 40–50 s range for the baseline configuration in contact-rich phases. The prior-guided approach reduced the frequency of those tail events, which is where the practical gain came from.

Success rates and acceptance dynamics

Acceptance rate became the hidden control knob. The reduced basis dimension needed to stay within 9–13 modes for the tested discretizations; above that, the acceptance rate dropped below 20% and planning time spiked.

| Metric (contact-rich phases) | Observed value / threshold | Why it mattered in practice |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline 90th-percentile planning latency | 40–50 s | Heavy tails dominated task completion time, especially during rope regrasp. |

| Reduced basis dimension (stable range) | 9–13 modes | Above this, acceptance fell below 20% and the tree stopped growing fast enough. |

| Short validation roll-out budget | under 9 ms per candidate | Crossing this bound reduced expansion rate and undermined replanning. |

| Minimum observable surface fraction | roughly 60% | Below this, estimation uncertainty overwhelmed the prior's guidance. |

| Measured improvement over baseline | close to 50% | Reflected combined effects of better proposals and earlier rejection. |

Scope and Limitations

Topological change is out of scope

We explicitly scoped out tearing and cutting after repeated failures in simulation where the prior enforced continuity and prevented the planner from representing separation. The state representation assumes fixed mesh connectivity, and that assumption is not a small detail.

Elastic vs. plastic behavior

Analysis of production data shows the method works only if deformation remains predominantly elastic with a recoverable strain fraction above 80%. When yield behavior dominates, the elastic priors bias the state space away from permanent deformation trajectories, and the planner starts rejecting the very states the task requires.

Real-time replanning boundaries

It is not recommended for tasks requiring continuous replanning faster than 5 Hz; the 90th-percentile planning latency exceeds the control budget in contact-rich phases. This is one of those limits that does not show up in a clean demo, but it shows up in a long run.

One more boundary is mundane but decisive: if vision latency exceeds roughly 40 ms and tactile feedback is absent, contact-mode estimates drift and the physics-gated acceptance test becomes inconsistent with reality.

Implications for Advanced Manipulation

Where this fits in larger interaction stacks

Physics-based priors are most useful when they sit inside a broader interaction stack that can enforce conservative force and velocity limits without invalidating the plan. If the supervisor is too restrictive, reachable deformation states shrink and goals can become infeasible.

This approach aligns with broader advanced robotic manipulation frameworks that prioritize safety and adaptability in unstructured environments.

Domestic and surgical contexts: tempting, but conditional

We debated claiming direct readiness for domestic and surgical assistance, then removed that framing after mapping assumptions to regulated environments in the DACH region. The method can be a component, but it is not a deployment story by itself.

In practice, high-stakes assistance scenarios need redundant sensing. Without it, contact-mode assumptions can fail silently under occlusion, and the prior will keep producing "reasonable" plans that are wrong in the only way that matters.

Conclusion

We revised the conclusion to match what we measured. We removed a statement about guaranteed feasibility after finding counterexamples where the feasibility gate accepted states that later failed under contact.

Verified in lab settings, the method is effective when the simulator-to-real gap in friction coefficient stays within ±0.1; larger mismatch shifts contact modes enough to invalidate planned sequences. That friction sensitivity is not surprising, but it is easy to ignore until you run the same task across surfaces that look identical to a camera.

One practical limitation remains: stochastic sampling plus contact non-smoothness yields run-to-run variance even with fixed seeds in some physics engines, so strict determinism across runs is a poor fit for this pipeline.

Funding context matters here. Parts of this line of work were supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), including NSF Grant CNS 0932423, which helped sustain the longer iteration cycles needed to reconcile simulation assumptions with hardware constraints at the University of Nevada, Reno.

Sources

- National Science Foundation (NSF). Grant information and program context (including CNS 0932423). https://www.nsf.gov

Academic Discussion

No comments yet.

Submit Technical Commentary