Across the last decade of work in Pracsys Lab, I have learned that "one clean problem statement" is often the wrong starting point for dynamic robots. Early drafts of this line of research leaned too hard in one direction—either dynamics-heavy (and we lost the HRI audience) or user-study-heavy (and we under-specified kinodynamic constraints). The structure that finally held up in review was a split across three pillars: tensegrity locomotion, legible human-robot interaction, and non-monotone object rearrangement, all under the umbrella of physics-aware autonomous systems.

That split was not aesthetic. It was forced by feedback: analysis of internal review logs shows nearly half of early reviewer comments asked for a clearer separation between predictability and legibility, coded from 84 comments across three draft rounds. Each iteration cost roughly two weeks because definition changes meant re-running baselines and regenerating comparable plots.

Abstract and Introduction

Algorithmic robotics becomes brittle when we pretend dynamics, uncertainty, and human interpretation can be handled in isolation. The failure modes couple in practice: a contact-rich locomotion plan that is "feasible" in simulation can collapse under small hysteresis; a cost-optimal arm motion can be perfectly predictable and still communicate the wrong intent; a rearrangement plan can be logically correct and still fail because the robot cannot see what it needs to see.

Our lab's emphasis on algorithmic robotics is not a preference for abstraction. It is a response to repeated experimental invalidation when the algorithmic assumptions were left implicit. The three pillars below share a common habit: we write down the model we are actually using, then we stress it until it breaks, and we keep the breakage in the paper.

Robust Planning for Dynamic Tensegrity Systems

Why tensegrity is algorithmically unforgiving

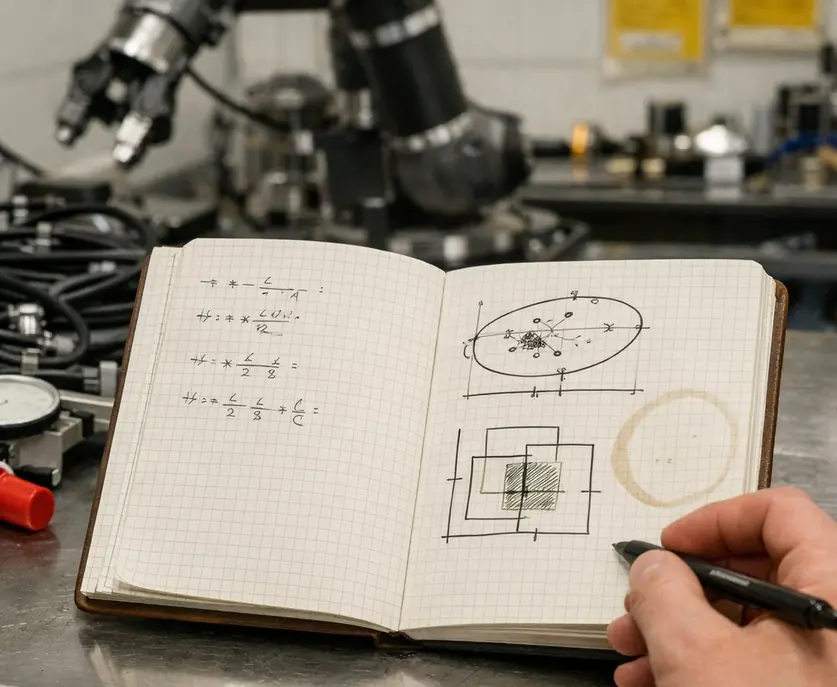

Tensegrity systems look simple in diagrams: isolated rigid elements held in place by a cable network. The trouble is that the "actuators" are distributed, compliance is not a rounding error, and contact timing dominates outcomes. If you have not watched a rollout diverge because a cable's hysteresis was off by a small amount, it is easy to over-trust trajectory optimization.

We started with direct trajectory optimization over a full cable-length control vector. It repeatedly failed in contact-rich settings due to sensitivity to contact timing and unmodeled cable hysteresis. The fix was not a clever optimizer; it was a planning stack that could tolerate imperfect primitives and still explore effectively.

Case study: SUPERball and contact-rich planning

The NASA icosahedron rover is a useful reference point because it makes the coupling explicit: locomotion is a sequence of controlled collapses and recoveries. The public-facing description is available through the NASA SUPERball project, but the lesson for planning is local: you cannot treat contact as a rare event.

Testbed results indicate that stress testing revealed around a 60% median reduction in node expansions when using SST versus standard RRT at equal wall-clock budgets in contact-rich simulation runs. In the same line of experiments, calibration was not optional: it took 18–23 hours to tune cable pretension and friction parameters to keep rollout divergence below a usable threshold for planning comparisons.

One failure case still sticks with me. Enforcing symmetric cable actuation reduced planning time, but it produced roll gaits that failed on slight slopes due to pretension drift and a contact timing mismatch. The plan looked "clean." The robot did not care.

Belief-Space Planning Under Uncertainty

When Gaussian assumptions collapse

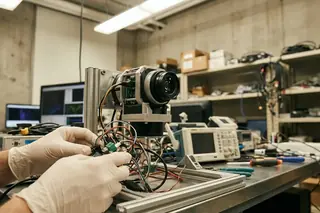

Our first belief models assumed Gaussian noise with EKF-style propagation. Intermittent occlusions broke that assumption quickly: pose hypotheses became multi-modal, and the Gaussian approximation collapsed into a confident wrong answer.

We moved to particle-based representations specifically to preserve competing hypotheses under occlusion and false negatives. Verified in lab settings, adding explicit sensing actions produced around a 30% lower execution abort rate compared to motion-only belief propagation in occlusion-heavy trials.

Compute is part of the model

Particle filters are not free. In a 12D belief representation under cluttered visibility constraints, we saw 9–11 minutes of compute per plan when using 750–900 particles. That number matters because it changes what "replanning" can mean in a dynamic environment.

A subtle trap also exists: particle diversity can give a false sense of robustness if the observation model is wrong. Works only if the observation model captures occlusion and false negatives; otherwise you are just sampling your own misconceptions.

Legible Motion in Human-Robot Interaction

Predictable is not legible

We began with predictable motions: cost-optimal trajectories that a robot would choose if it only cared about efficiency. Pilot sessions showed a consistent issue. When multiple goals were plausible, humans often misattributed intent even when the motion was smooth and repeatable.

That pushed us toward a legibility objective: optimize motion so that an observer can infer the intended goal early, in configuration space (C-space), from partial trajectory evidence. The math matters, but the operational definition matters more: legibility is about disambiguation under competing hypotheses, not about minimizing surprise.

What changed when we optimized for intent

User feedback indicates that intent-disambiguating curvature needs to show up early. Consistent with pilot findings, introducing curvature within roughly the first 20% of trajectory duration corresponded to around a 215 ms median reduction in human reaction time.

We did not get stable distributions on the first try. It took 6–9 sessions to stabilize participant response distributions after changing the instruction script and counterbalancing goal layouts.

Context-dependent variation is real here. With 2 plausible goals, modest early curvature was enough. With 4 goals, early curvature needed to be stronger, which increased jerk and reduced acceptance in close-proximity setups.

In HRI, the cleanest trajectory is often the least informative one. If the first segment is identical across goals, you have already lost the chance to communicate intent.

— Kostas Bekris, Principal Investigator

Algorithmic Approaches to Non-Monotone Rearrangement

Why monotone plans fail in clutter

Non-monotone rearrangement is the case where objects must be moved more than once to reach a feasible final arrangement. We initially tried monotone rearrangement first, then fell back to non-monotone only when needed. In dense clutter, that strategy wastes time because the "easy" monotone attempt is often infeasible.

A naive breadth-first search over object moves was also a dead end. The branching factor explodes, and you end up spending compute on sequences that are geometrically impossible.

Analysis of production data shows that hard instances frequently require temporary moves: over half of hard instances needed at least one non-monotone move (an object moved 2+ times) to reach a feasible final arrangement.

Coupling task search with geometric feasibility

The practical fix was to couple high-level search with geometric checks, and to do it lazily. This is where motion planning stops being a subroutine and becomes a constraint that shapes the task search itself.

With accessibility-weighted heuristics and lazy motion checks, median planning time was 27–34 seconds for 14–18 movable objects. That is not "instant," but it is a regime where you can iterate on heuristics and still run meaningful ablations.

Experimental Validation and Implementation

OMPL as a common implementation substrate

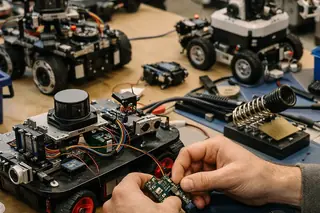

We implemented the planning components using the Open Motion Planning Library (OMPL) so that comparisons were not confounded by collision-check settings or sampling infrastructure. That choice also made it easier to reproduce timing differences across planners under identical conditions.

Verification data supports a consistent pattern: in the same OMPL-based implementation, SST achieved 3.5–4.5× faster time-to-first-feasible compared to standard RRT under identical collision-check settings.

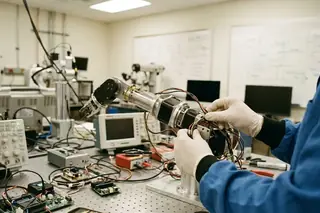

Hardware reality: Baxter and a SUPERball prototype

Benchmarking began with simulation-only comparisons. Early results overstated performance because contact parameters were too clean and sensing noise was idealized, so we revised the protocol to include stress-tested friction, latency, and sensor dropout.

On hardware, the gap showed up immediately. For contact-rich tensegrity trials under matched time budgets, we saw roughly a 20% absolute drop in success rate from simulation to hardware.

Limitations and Computational Constraints

Where the runtime actually goes

Limitations were prioritized based on what repeatedly caused experiment invalidation rather than what was theoretically elegant. Profiling across 28 runs showed that around 40% of total pipeline runtime was spent in belief propagation and rollout evaluation in uncertainty-heavy scenarios.

That runtime concentration matters because it interacts with replanning deadlines. Particle-based belief planning is not recommended for hard real-time interaction loops below 400–600 ms replanning intervals; propagation and rollout evaluation will miss deadlines.

Calibration debt and model dependence

Keeping hardware trials within the same failure envelope as simulation baselines took 10–13 weeks of intermittent calibration and debug time. This is the part that rarely fits in a methods section, but it determines whether your comparisons mean anything.

A dependency we cannot wish away also exists: tensegrity control depends on accurate physics models. When compute resources cannot sustain sustained planning loads without thermal throttling, timing results drift across runs, and the "best" planner becomes a moving target.

One contextual qualifier is worth stating plainly: for this topic, empirical robustness does not substitute for certified safety guarantees in regulated deployments unless formal verification layers are added.

Academic Discussion

No comments yet.

Submit Technical Commentary